For the last five weeks, I have been doing multiple daily injections (MDI). This was the longest time that I have ever been on MDI in my life. After years of twice-daily split-mixed injections with regimented routines of breakfast – snack – lunch – snack – dinner – snack, I opted to get an insulin pump at age eleven because I wanted to sleep in on the weekends. I have been using a pump of some sort ever since for a total of 24 years so far.

I decided to try basal-bolus injections around eight years ago because I had never done it, and I wanted to see what people go through when using this treatment method. I hated it. The constant stabbing myself with pen needles. The added layer of deciding if a snack was worth an additional injection. Having to carry around insulin pens and pen needles everywhere I went. I know that many people love MDI and achieve great results. But eight years ago, it just wasn’t for me.

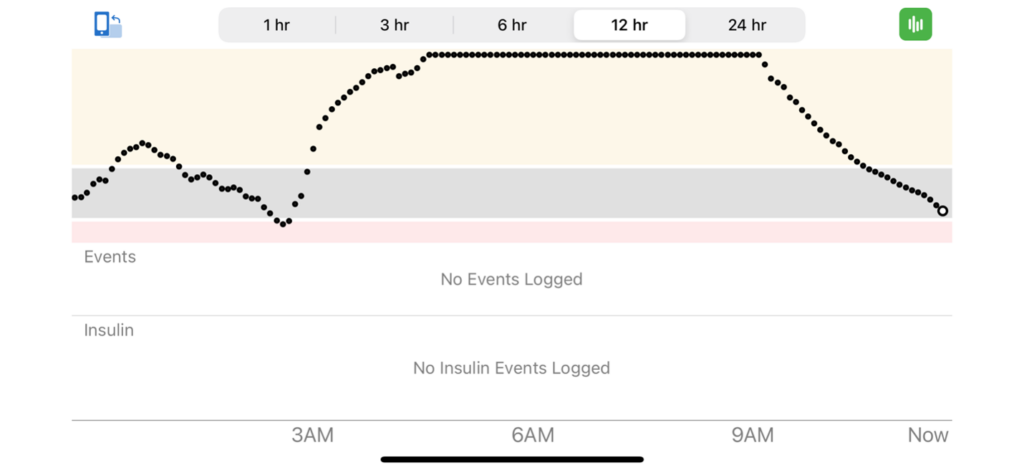

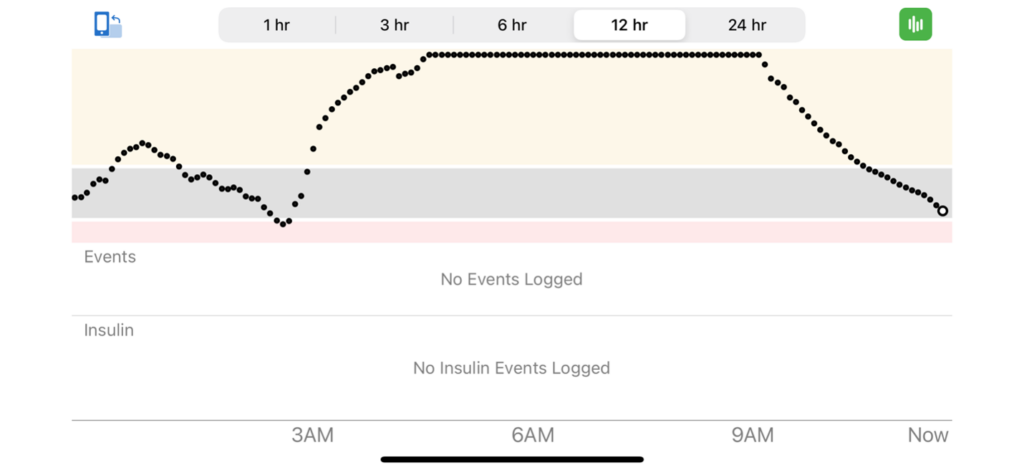

But when I found myself exasperated after having high blood sugars for seemingly no reason on and off for about a month, I loudly declared that I was going manual mode, meaning basal-bolus injections. I was fed up and decided that my best bet was having a long-acting background insulin to keep my blood sugars from running so high all the time. Here’s the Dexcom data that shows the straw that broke the camel’s back for me.

Scar Tissue and “Real Estate”

As I had been wearing a pump for so long, I figured that maybe the issue was scar tissue from repeated infusion set wear on my abdomen. I’ve been attempting to use other parts of my body for years and focusing more on it in the last year especially to no avail. I have tried my arms with running the tubing down my shirt, my legs, and my buttocks to give my abdomen time to rest. None of them have been particularly positive experiences.

But when you’re taking injections, it’s much easier to give the insulin in the arms and legs, and I could avoid my abdomen completely. It also means that you don’t have an insulin pump and tubing attached to you at all times. This was surprisingly very enjoyable for me, much more so than when I tried MDI eight years ago. I loved only having my Dexcom CGM to worry about when it came to keeping devices attached to me.

Logistics and Low Carb Meals

I haven’t minded taking the injections for the most part, though I can tell when I should change my pen tip or get a new syringe for sure! It’s been nice to not think about where to clip my pump when I’m going to bed. And packing for travel – WOW! I only had to take syringes, pen needles, insulin pens, and sensors. It was SO nice to not have to pack the loads of pump supplies I usually need to travel.

The biggest challenge, however, is remembering to carry my rapid-acting insulin with me when I leave the house. Just the other day, my husband took me to lunch and I forgot to put my insulin in my purse. I didn’t realize this until after I ordered, and I didn’t get to eat my chia pudding until I got home. It was a bummer. Other times, I have realized while in the car that I didn’t bring it and have had to alter my meal plan to be very low carb.

To be honest, after the morning I woke up from being HIGH for hours, I was scared to eat carbs. This was a new experience for me, this fear of carbohydrates. But I was so tired of having high blood sugars that I was afraid to eat anything that could shoot me right back up to the range where I feel like garbage. I ate very low carb for about a week after that day, which was not easy for me as a longtime lover of carbs. I gradually resumed my usual diet over the next couple of weeks until I made it (almost) back to normal.

Insulin Dosing

When it came to figuring out how much basal insulin to do, I tried the same dose as my total daily basal for the first night. This turned out to be not enough, which was to be expected, but I was nervous about overdoing it. I went up two units every night for a few nights and ended up needing 25% more basal insulin with injections versus the pump. I also had to do more bolus insulin, making my carb ratios and correction factors more aggressive.

If you’re ever in the position where your pump breaks or you need to do injections, always start with the doses from your pump. It’s a good idea to make sure you know what your basal rates, correction factors, and carb ratios are so that you aren’t going in blind. This could mean uploading your pump every so often, which you may already be doing at your diabetes care visits. It could also be taking photos of your pump settings or simply writing it down. You could also reach out to your healthcare providers to ask for guidance.

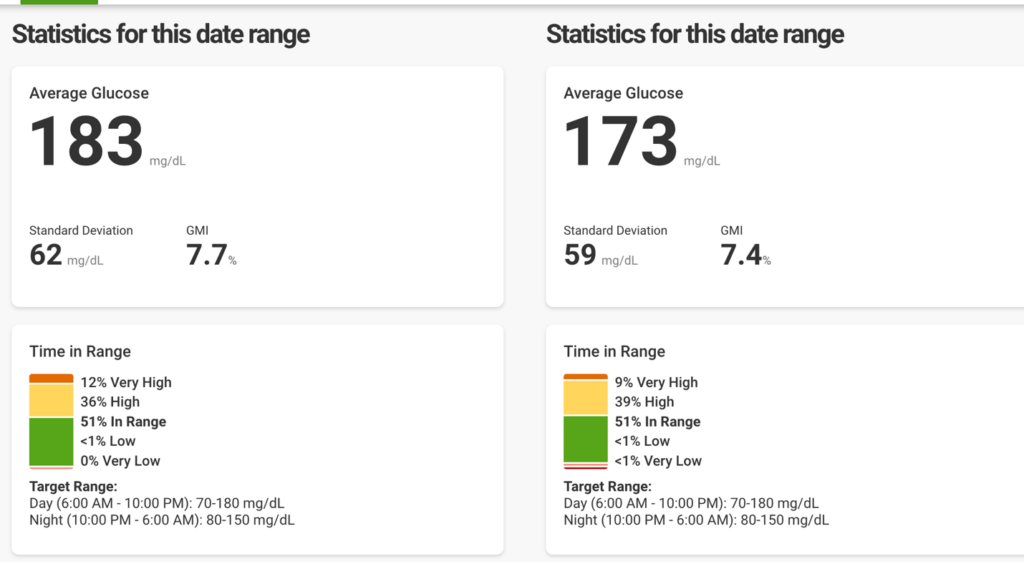

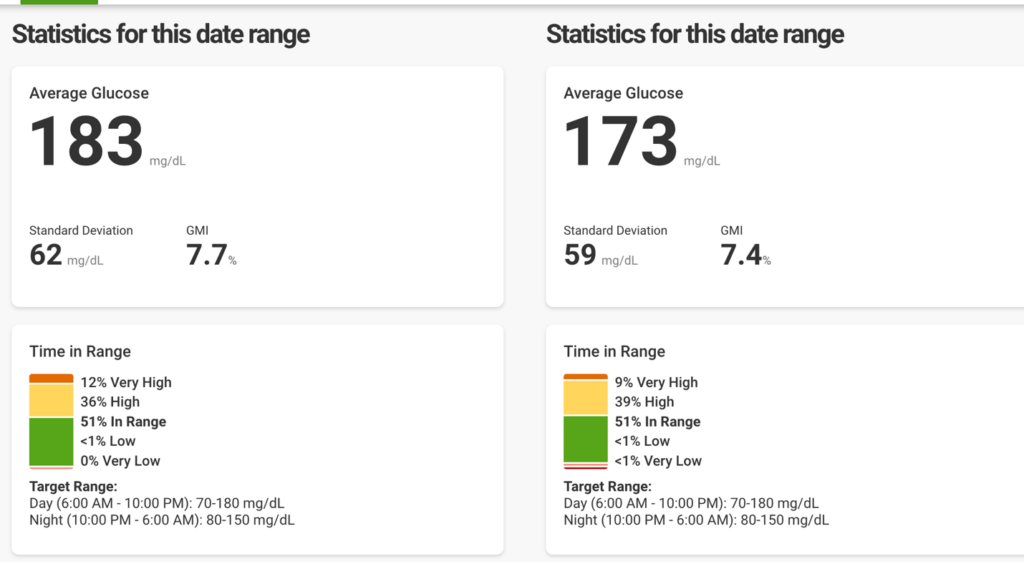

Control-IQ versus Injections

As it turns out, I had similar time in range, time above range, and time below range on Control-IQ and injections. Normally on Control-IQ I would have time in range closer to 65-75%, but for some reason I am having more high blood sugars than I typically have. And it looks like the injections did the trick for a couple of weeks but wasn’t as good as I was hoping it would be from the standpoint of time in range.

It did allow me to give my abdomen some much needed rest, which I plan to continue to do regardless of if I’m using my pump or injections. I am hoping to let it rest for 3-6 months to allow any scar tissue to heal. It was also much more enjoyable than I expected it to be. I loved the freedom of being unattached to the tubing and pump. The best part was how little I needed to pack when traveling to Berlin for ATTD.

Back to Control-IQ

Now that it’s been a full five weeks, I am ready to go back to only one injection every three days, along with low-suspend, decreased basal rates when dropping, and automatic corrections when I’m high. I also feel a renewed confidence in my ability to handle manual mode if needed. Of course, it was not entirely manual mode; I still had my trusted Dexcom, allowing me to see my glucose levels and trends.

I’m not sure if I’ll still be having the annoying highs like before as I hook myself back up or not, but I’m ready to try again. When you’ve lived with diabetes for a long time, you have to do whatever you need to do to keep your resilience. Because diabetes doesn’t quit, but neither do you.

Written and clinically reviewed by Marissa Town, RN, BSN, CDCES